An accessible, scientific explanation.

At the end of this week’s episode of Aikatsu Friends, something very strange happened. I was at first elated that Aikatsu would reference my area of neuro research, turning around and incorporating a part of my thesis topic instead of me simply trying to bring Aikatsu into my life’s work. But then I was double facepalming hard as the scary music played and everyone started freaking out about Mio entering the zone. Either you took it at face value and were excited/exasperated at this new and interesting development, or you were as confused as me as to how the writers messed up something so simple. Which is why I want to take it upon myself to talk a little bit about the zone and what it is in real life, both for beginners and intermediate viewers. I consider myself somewhat of an expert on the topic, and while you can probably just skim the wikipedia article on it, I’d like to present my take on it in the context of Aikatsu.

What is “the zone”?

The “zone” is the commonly known name for the mental state known as “flow”, researched and popularized by an American-Hungarian scientist with a very long and hard to pronounce name. Flow is defined as “effortless attention, reduced self-awareness, and enjoyment that typically occurs during optimal task performance”. As Tamaki-san explained, it’s often used in the world of sports, but also finds widespread use in fields as varied as music, programming, and even translation. During flow, task performance (or idol performance, in this case) is at or near a peak. It feels good to be in a flow state, and you enter a feedback loop of focusing more to do better, and doing better because you’re focusing more.

How can I get into flow?

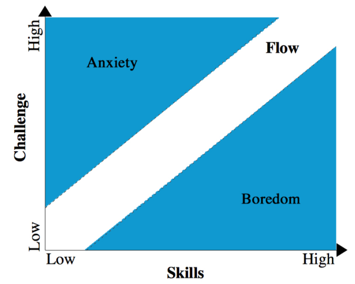

Flow occurs naturally when skill level and task difficulty are perfectly matched. Take a look at one of my favorite graphs below.

Flow can (but does not necessarily always) occur throughout the entire white diagonal area. You’ll notice that when skill level is higher than the challenge it can lead to boredom and disengagement from the task, whereas when the difficulty is too high it can lead to anxiety or distress. It’s also wider than just a single line, indicating that there’s some wiggle room between skill and challenge, and a small range of each that match up can induce flow. Studies have shown that on average, it takes 30 minutes of uninterrupted performance for a skilled practitioner to enter flow, and that any external disturbance can not simply reset this timer, but increase it depending on the lasting aftereffects of what happened. There’s also this long list of bullet points on what else you need, but you can read the wiki article yourself if you’re interested.

What are the downsides of it?

Contrary to Tamaki-san, Mirai, and Karen’s extremely horrified reactions, flow in real life has nearly no downsides. It feels good, it makes you better, and it improves the results of whatever you’re doing. In fact, a huge portion of my research is based on how we can more effectively lead people into a flow state to optimize learning complex tasks. If I had to guess what the big deal is, I’d say it may be related to some things normally considered beneficial. For instance, people in a flow state shut out their surroundings that are irrelevant to the performance at hand in order to concentrate more deeply on it. But in terms of physical or mental strain, there’s nothing. Flow doesn’t take more energy from your body, and it doesn’t leave you feeling drained mentally or emotionally. On the contrary, it can leave you feeling elated or satisfied and full of confidence, exactly what Mio demonstrated after her live. Hmm…

Give me more science please (optional section)

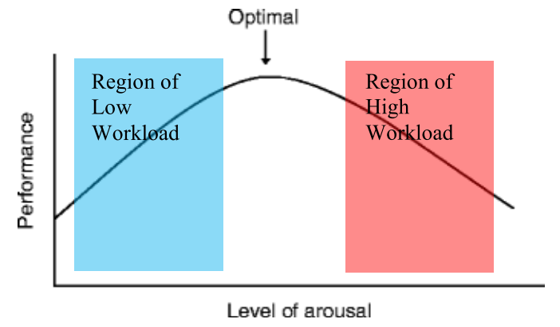

You got it, honeys. When performing any task (and we use this term very generally, meaning anything that requires attention and action, or some kind of response), you can also measure the associated cognitive workload. Workload has a few definitions, but here I mean it as a correlate of the limited information processing capacity of the brain, with the maximum cap related to each individual’s working memory. Given a specific task with a set challenge level, skill/expertise becomes the only independent variable. Check out the figure below.

Performance is self-explanatory, but above just replace arousal with workload as in this case they’re equivalent. On this inverted U-shaped graph, the left side represents high skill level and the right is low skill level. And right in the middle, in the familiar white space from far above, is the area of flow activation. Therefore, when workload is at a Goldilocks level and performance is at its maximum, one can enter flow.

How do we make use of this information? First we need a way to measure cognitive workload. You can do this in several ways: direct performance measurements, secondary task performance, subjective surveys, or with neurophysiological measurements. It’s this last one that my lab is interested in. It encompasses things like heart rate and skin conductance, and also recordings of the brain using a variety of machines (my focus is on fNIRS, a topic far too complex for this post). This also allows for completely independent and objective measures of workload without interfering with the person doing the task. By analyzing workload and performance in real time, task difficulty can be adjusted to nudge a person into that sweet, sweet flow zone, thereby optimizing performance and making learning more efficient.

How will this affect Aikatsu?

We know that flow is good, so why is the Aikatsu Zone so dangerous? Let’s first look at the problem Mio let us in on at the beginning of this episode. She’s feeling inadequate because she feels like she isn’t changing like everyone else is. In other words, she’s not improving as quickly as them. But this is completely natural for someone who’s already as skilled as her. People learning a skill go through alternating periods of improvement and periods of stagnation. When you’re just starting out, these go back and forth very quickly, and it feels like you’re overcoming every obstacle in your way with little effort. Just look at how fast Aine got better at acting with Mirai or encouraged Chiharu-san to start her brand. Now compare that to the much higher amount of time and effort it took Honey Cat to boost their Friends Appeal to the next level. And don’t even get me started on Love Me Tear, who has shown no visible change at all yet. Mio just needs to understand that there’s nothing wrong with her, and she’ll improve as long as she keeps on ganbaru-ing.

Now what might happen because of Mio’s Aikatsu Zone? Let’s go back to one of the effects of being in the flow: increased self-confidence. Look at the language Mio used towards the end of the episode. “I feel like I can reach them. I feel like I can surpass Love Me tear.” It’s even apparent in the preview when she’s talking to Aine. “I’m on top of my game. Just leave it all to me.” She’s so focused on herself that she appears to be losing what makes Friends special in the first place. I can see only one of two outcomes happening in the Brilliant Friends Cup.

1) Pure Palette loses because Mio goes too far on her own, throwing their balance off.

2) Pure Palette wins, but entirely due to Mio’s efforts. None of the other competing Friends appreciate this, and Aine feels betrayed and useless.

This also stems from the flow state making you naturally shut out your surroundings, which when performing on stage could mean both the audience and the person singing and dancing right next to you.

So hopefully that was a good explanation for those of you unfamiliar with the concepts, and provided some insight about my views on it all and how it relates to Aikatsu. I write a whole thing for every single episode, but rarely do I share it here because I like seeing everyone’s unbiased opinions. It’s just that in this case, when it’s a concept so clearly tailored to me, I can’t keep my mouth shut. Don’t forget to keep in mind that nothing I said may be relevant at all, since this is a fictional world that doesn’t necessarily follow the rules of ours. I’m excited to see where they take this, and hope deeply that it’s not dropped in two or so episodes after the Brilliant Friends Cup, as this could be a really interesting and unique plot thread.

This is really interesting! For a second I thought they were introducing some new supernatural idol powerup to the series, so it’s good to know it is based in reality.

About the concern show by Tamaki-san and Love me Tear, maybe it’s because they know and/or have experienced the sudden overconfidence and “isolation” that the Aikatsu Zone may cause, and fear that Mio-chan is going to mess up just like in the outcomes you suggested.

Let’s see where they go from now on, Mio-chan is my favorite so I’m really liking this development!

It reminded me of Kuroko’s Basketball. I laughed when we saw Karen and Mirai talking about it like it was some tangible, visible thing, but maybe it’s more real than I thought after all.

“I write a whole thing for every single episode”

You can’t just say this and not expect someone to ask that you start sharing them!

I wonder if Tamaki, Karen and Mirai are worried because of something that may have happened in the past. Kinda like the school principale in Stars, but rather than some kind of life-sapping mysterious power like Yume’s, this could develop into a more “evil” scenario.

I remember how in Kuroko’s Basket, Aomine seemed to make it a point to not just defeat his opponents, but specifically crush them in order to shatter their confidence in themselves.

If Mio used the zone to go that far against other Friend units, possibly in a bid to gain enough strength to surpass Love Me Tear (or perhaps even involuntarily, since being in the zone shuts you down from your surroundings), I could see the other characters not taking it very well, especially Aine who insists that everyone who does idol activities with them must be one of her million friends.

This is 99% the same reason it was bugging me, too. I just hope they find a way to make it good and not as misinformed, random and silly as it comes off. If they’d introduced this concept maybe twenty episodes ago and not within the same minute of us hearing about it for the first time it might have been remotely believable.

If they find a way to make it like Gundam’s Newtypes or something I honestly won’t care and might even find it fitting with Aikatsu, but at the time, I was really not convinced by the provided explanation and I thought it was so bad and cheesy that it made me laugh IRL.

I really appreciate your insight on the topic for the people who didn’t catch that particular bit. However, personally I think Tamaki, Mirai, and Karen were not “horrified”, just “serious”, in the sense that they know this is most likely going to have consequences, so, for me, it didn’t ruin the moment at all.

Again, thank you for this kind of posts, I’m happy to see that I’m not the only one thinking deeply about Chinese cartoons.

I’ll be honest. When they did the whole “zone” thing, I just loudly groaned. Every show I’ve ever watched that referenced the zone, degraded at that point. Everything became about entering the zone. Like it was something that could be turned on and off with the flip of a switch. They never shut up about the damn zone. Then within a couple episodes, EVERYONE is flipping the zone switch like nothing. I really hope it doesn’t happen here, because I just find that so annoying if it’s not limited to a very short arc.